Dressing Up

Click here for exclusive pictures included in this magazine.

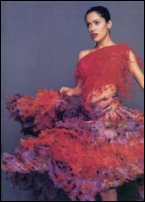

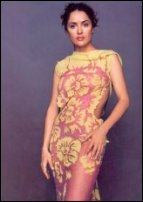

Salma Hayek has heard the stereotypes about Latin actresses - and destroyed them all. Here, she wears the best of

Paris haute couture and talks with Vanessa Friedman about her two new movies, her life off camera, and her passion for fashion.

Photographed by Gilles Bensimon

It doesn't seem possible. Five-foot-two-inch Salma Hayek, curvy as a mountain pass, in the same dress as that towering, willowy Russian model Natalia. Common sense

says this is one costume drama that is not going to happen. Yet here is Hayek, silhouetted against a gray backdrop in a studio somewhere in the far reaches of Paris's Fourteenth Arrondissement, in the very same laced, fishtailing, paint-splotched Christian Dior dress that

came down the couture catwalk on Natalia. And looking - well, logic-defying.

Of course, this shouldn't really come as a shock. After all, for the last nine years, ever since she hit Hollywood at age twenty-two, a tiny unknown, speaking barely any English, Hayek has been the exception that breaks the rule. She's a firecracker of an actress in a bombshell's body, and she has made a practice out of dynamiting expectations and debunking stereotypes.

Like the one she first encountered when she arrived in Hollywood - and which she's previously voiced definitive opinions about: "Latinas get cast as maids."

During her eleven-year career, Hayek has never been cast as a maid on the big screen. In Mexico she achieved fame as a soap star, and in the U.S. she made waves as a sexy bookstore owner in Robert Rodriguez's Desperado;a wannabe nightclub star and coat-check girl in 54; and a muse-cumstripper in Dogma (to name just a few). She's about

to make her mark again this month as a young woman trying to break into Hollywood in Time Code, Mike Figgis's experimental film about Tinseltown (it was fully improvised and shot with a hand-held digital camera in one continuous take), and, in September, as a detective on the trail of accidental criminal Steve Zahn in the comedy Chain of Fools.

In neither of the latter films does she wear either a literal or metaphorical ruffled appron; rather she is strong, resonant, and surprising.

Which brings us to stereotype number two: "To be successful, you need to give the audience what it wants."

When it comes to Hayek, what the audience wants (at least the male part of the audience) is obvious. Hayek - getting her makeup redone between shots - has this to say on the matter: "I'm well aware most of the audience prefers me a certain way, at least when I am out in public. What way? Dressed as a nun, of course. Okay, maybe not," she says, laughing. "But just as I try to play different roles,

I have different personalities. Sometimes I want to be austere and strict, like when I wore the Alexander McQueen coatdress to the premiere of The Faculty, sometimes I feel girlish and want to wear a flowery dress."

"I'm a bit of an abstract figure that people can project their fantasies on; it's pretty much what we all are, otherwise we wouldn't be stars, and people wouldn't be interested. But people project things on you that have nothing to do with what you really are, or they see a little something and then exaggerate it. And you can't really control that. Robert Rodriguez saw me as very sexy for Desperado, but that's not the only thing that I am."

Which brings us to stereotype number three: "Serious actresses don't take fashion seriously."

"I want to know where that comes from!" snaps Hayek, in the midst of swapping the Dior for a second-skin Versace. As it turns out, this assumption really bugs Hayek. This assumption deserves a rebuttal. And ultimately it isn't just about clothes. Hear her out: "Who says if you are a serious actress you cannot be sexy or beautiful or like clothes? I like clothes, and I think I'm a serious actress. When I first came to Hollywood, one of the stereotypes I encountered - truly, there are so many

you could fill books - but one of them was that Latinas were tacky and had no sense of style. That wasn't my reality, it's not what I knew, so I made it a task for myself to change that. I went out and started working with designers when they didn't want to work with me; I went to fashion shows before that was trendy. In fact, the first fashionshow, I wasn't invited by the designer, I wasn't outfitted by them - I bought my own dress. Now it's changed. I've been lucky enough to wear couture in real life, for awards ceremonies and

the like, and it's wonderful, because it makes getting dressed, which for me is a very feminine ritual, even more special: You're careful about the shoes, the bag - it does something to your mood. But I always liked fashion."

"I want to know where that comes from!" snaps Hayek, in the midst of swapping the Dior for a second-skin Versace. As it turns out, this assumption really bugs Hayek. This assumption deserves a rebuttal. And ultimately it isn't just about clothes. Hear her out: "Who says if you are a serious actress you cannot be sexy or beautiful or like clothes? I like clothes, and I think I'm a serious actress. When I first came to Hollywood, one of the stereotypes I encountered - truly, there are so many

you could fill books - but one of them was that Latinas were tacky and had no sense of style. That wasn't my reality, it's not what I knew, so I made it a task for myself to change that. I went out and started working with designers when they didn't want to work with me; I went to fashion shows before that was trendy. In fact, the first fashionshow, I wasn't invited by the designer, I wasn't outfitted by them - I bought my own dress. Now it's changed. I've been lucky enough to wear couture in real life, for awards ceremonies and

the like, and it's wonderful, because it makes getting dressed, which for me is a very feminine ritual, even more special: You're careful about the shoes, the bag - it does something to your mood. But I always liked fashion."

"When I was a very little girl, I mean little, four our five, my parents brought me back a trench coat from one of their trips away. I grew up in a tiny Mexican town, and it was hot - much too hot for the coat. But I always wanted to wear it to school, and I would have huge fights with my mother about it. I was always opinionated about what I wore. When other kids were getting excited about toys, I would get excited about clothes.

I liked to go to the closet every morning and pick what I would wear that day. I got joy out of it. I still do - I'm not conscious about, `Today I am doing this, so I will wear this.'For me, clothes aren't about a role I play - `star'- but a mood."

"On-screen," she continues, "clothes are like the icing on the cake of a character. In a period piece such as 54, costume becomes more important, because that was a very specific place and era that marked a very specific fashion. What you wear can transport you through time. In Wild Wild West, those corsets in no way let you forget where you were. But it needs to be accurate. In Chain of Fools, I wear a black leather jacket and pants, clothes that are just simple and comfortable. Sometimes you see a movie where the policewoman or mailwoman is very chic and

elegant, and it's obviously fake. Much as I am tempted by fashion, and I am, it's more important to stay close to the reality of the character."

This might lead to expect (it led me to expect) that on a photo shoot, which is a kind of a middle ground between real life and film, Hayek would create a character that fit the clothes. And indeed, perched on a wooden box, a fantastical feathered hat on her head, she starts to coo; in a sweeping flowered skirt and midriff top, she stamps her feet and tangos; in a `40s trench dress, she cocks an eyebrow and smolders. Ah! I think: She's a bird, a senorita, a star, she has lost herself in the moment. But then she explains.

"Of course, you also have to think about: Well is the feather in my face? If I turn my head will you see my hair?" she adds. "There are technical considerations with a still camera; it's much more of a collaboration. You establish a relationship with it. In film, you have to maintain this tiny awareness, but mostly you want to detach yourself from the camera."

Watching Hayek turn her shoulders three quarters to the right and drop her eyelids to half mast; watching her position herself just so by the wind machine; and watching her carefully considered movements, it's not hard to conclude that her awareness of the camera is very high.

"I'm pretty damn familiar with the camera now. I've been doing this since I was nineteen. But you also have to be brave and try different things because, let's face it: What was beautiful seven years ago isn't necessarily beautiful today. I have a lot of things that could have been limitations, starting with my height. But I wouldn't accept them. I just refused."

© Transcript by Jacinda, webmistress of HayekHeaven

|