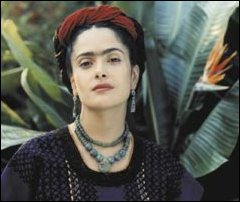

Salma Hayek is Frida - The Two Fridas

By Stephen Farber

Source: www.thebookla.com

In a famous self-portrait, Mexican artist Frida Kahlo

stands alongside her famous husband, Diego Rivera.

He towers over her; she looks almost like a child

trapped in the grip of a huge, bearish figure. But that

image is deceptive, because Frida has proved to have

a power that belies her diminutive stature. Although

she painted in obscurity during much of her life, in

recent years her reputation has grown and now

equals that of her celebrated husband. Her striking

self-portraits of a damaged but defiant woman clad in

colorful Mexican garb have caught the imagination of

the entire world. Kahlo has become a feminist

icon--the epitome of the woman overpowered and

victimized by a potent man but gradually emerging

from his shadow. She now stands as one of the most

revered women artists of all time.

The saga of the film project based on Kahlo's life is

strangely analogous to Frida's own life story. This film

has become the driving passion of several women

who lack the clout of their male counterparts in

Hollywood but have persevered in pursuit of their

dream. "Anyone else would have given up by now,"

says Salma Hayek, the actress who is determined to

play Frida. "But I've been obsessed with this project

for eight years, and I know it will be made." If Frida

Kahlo's personal journey encompassed an unlikely

triumph against adversity, the women behind the

movie have survived some heroic struggles of their

own.

The first champion of the movie was Nancy Hardin,

who had spent a decade as a New York book editor,

a literary agent in Hollywood, then one of the first

important female studio executives. In the mid-80s,

Hardin was looking to make the transition to

independent producing, and she learned about a new

biography of Frida Kahlo by Hayden Herrera. Kahlo,

who had died 30 years earlier, was at that point

virtually unknown. But after a dinner with Herrera's

agent, Hardin perused the biography and found

herself compelled by Kahlo's amazing life story. As a

child Frida Kahlo spent a year afflicted with polio. At

the age of 18, she was struck by a streetcar, and her

spine was broken in several places. The accident

damaged her reproductive organs, and the theme of

impaired maternity became one of the most potent

motifs in her art.

As a result of her injuries, she also had to undergo several more

operations later in life. Two years after the accident, Frida went to

show her early work to Diego Rivera, who was already Mexico's

leading artist. He left his wife to marry her, and the two became

involved in a complicated, tempestuous love affair that lasted until

Kahlo's untimely death at the age of 47. "They both had generosity

of spirit," Hardin says. "As difficult as Rivera was, he was always

encouraging toward her art. There was no envy on his part. On the

contrary, he always said that she was a greater artist than he was."

Rivera was, however, incapable of monogamy, and Kahlo was hurt by

his infidelities, especially when he began a furtive liaison with her

younger sister. She divorced him but then remarried him a year

later. She had her own extramarital affairs, including one with

socialist leader Leon Trotsky, and she also dallied with several

women. Hardin came to see Frida's story as an emblematic tale for

women torn between marriage and career. "I thought her dilemma

was very contemporary," Hardin says. "Although she was very

passionate about her relationship, it did not interfere with her work.

She was determined to live fully in every area of her life."

After she optioned the rights to Herrera's book in 1988, Hardin tried

to sell it as an epic love story in the tradition of Out of Africa.

"Mexico in the 30s was like Paris in the 20s," Hardin says. "It was a

period of tremendous cultural and political ferment." Hardin

contacted the hottest actresses of the period, including Meryl Streep

and Jessica Lange, and although they expressed interest, they were

reluctant to make a commitment before a studio had officially

purchased the project. "But nobody at the studios had heard of Frida

at that time, and there was no interest in Latin America," Hardin

recalls. For the next couple of years, she sent the project to every

studio in town, but every single one rejected it.

Gradually, however, the interest in Latin culture began to blossom,

and Kahlo's art came tobe revered in feminist circles. In May of 1990

one of Kahlo's self-portraits sold at Sotheby's for $1.5 million, the

highest price ever paid at auction for a Latin American painting.

Around the same time, Madonna bought two Kahlo paintings and

announced her plans to star in a film based on Frida's life. Other

producers jumped on the bandwagon. Robert De Niro's Tribeca

Productions envisioned a joint biography of Rivera and Kahlo.

Director Luis Valdez, best known for his film of La Bamba, sold a

project to New Line and rushed to put his film into production in the

spring of 1991. But protestors objected to the casting of non-Latina

Laura San Giacamo as Frida, and New Line bowed to the controversy

and dropped the film. Within a few years Hollywood had gone from

complete ignorance of Frida Kahlo to an insane feeding frenzy.

"When I first tried to sell the project," Nancy Hardin says, "there was

no interest because nobody had heard of Frida. A few years later, I

heard the exact opposite--that there were too many Frida projects in

development, and nobody wanted mine."

Nevertheless, Hardin persisted. Eventually she persuaded HBO to

option Herrera's biography for a cable TV movie. At HBO Hardin

partnered with Lizz Speed, a rising young development executive

and producer. Speed had gotten her start in Hollywood by working as

an assistant to one of the town's most powerful women, Sherry

Lansing. A few years later she joined director Brian Gibson, who had

just completed What's Love Got to Do With It, the story of Tina

Turner, another woman subsumed by a powerful man. Gibson had

also directed The Josephine Baker Story for HBO, and the network

hoped he might sign on to helm Frida. But the movie was difficult to

cast, because there were no Latin actresses with box office clout in

the early 90s. Although the project languished at HBO, it developed

another powerful advocate in Speed, who became inflamed by the

cinematic possibilities of the Kahlo biography.

"I was attracted by her will to persist, her refusal to settle for

mediocrity," Speed says. "She had such an insatiable appetite for

life. To me her art was secondary to the strength of her spirit.

Besides that, Frida's story raises questions about how two

larger-than-life people stay married. Rivera was incredibly

promiscuous, but he never tried to hide it. I saw him as an honest

dog. Through it all, he and Frida were always respectful of each

other. They grew together and ultimately had a strong marriage."

Speed's passion for the project helped it through its next difficult

transition. After four years in development, it became obvious that

HBO had grown hesitant to make the movie. Speed and Hardin

managed to get it away from HBO and sell it to Trimark, a small

distribution company that was looking to change its image and cash

in on the booming indie film movement. "They were shifting from

exploitation pictures to classier films like Eve's Bayou," Hardin says.

"They liked Frida because it would give them arthouse cachet along

with a hot, sexy actress."

That actress was Salma Hayek, who became attached to the project

when it moved to Trimark. A few years earlier Hayek's name had

been mentioned as a possible candidate to play Frida, but at that

point, she was an unknown commodity. By the mid 90s, however,

she had starred in a few moderate hits--Desperado, From Dusk Till

Dawn, and Fools Rush In--and Trimark wanted to be in business with

her. Hayek had been fascinated by Kahlo's work from the time she

was 13 or 14. "At that age I did not like her work," Hayek says. "I

found it ugly and grotesque. But something intrigued me, and the

more I learned, the more I started to appreciate her work. There was

a lot of passion and depth. Some people see only pain, but I also

see irony and humor. I think what draws me to her is what Diego saw

in her. She was a fighter. Many things could have diminished her

spirit, like the accident or Diego's infidelities. But she wasn't crushed

by anything." Hayek had heard about the other Frida projects, but

she resolved that no other actress would play the part. "This movie

should be played by a Mexican," she insists. "In a way Frida was like

Mexico--her body was broken, but she had a strong spirit."

Just when the project finally seemed close to production, it hit

another roadblock. The Trimark executive who championed it, Jay

Polstein, left the company, so Frida lost its strongest executive ally.

Hayek was frustrated and secretly took the project to Harvey

Weinstein at Miramax. Weinstein liked to nurture young actors, and

Hayek was one of the rising stars in the Miramax stable; the

company had financed many of her early pictures. Miramax was of

course the premier house for venturesome independent films, and

Weinstein immediately responded to the idea of actually producing

the Frida Kahlo project that had been the talk of Hollywood for a

solid decade. Miramax bought it from Trimark and hired Hayek,

Hardin, and Speed, along with Jay Polstein, to produce the picture.

"It cost Miramax a huge amount of money to secure the rights,"

Hardin says gratefully. "But it was Salma who pushed it through."

"Sometimes producers are wary of working with actors," Speed adds.

"But it's been great with Salma because each of us can take turns

being the cheerleader for the project. When one of us gets drained,

one of the others can take over and push for it."

Just when the project finally seemed close to production, it hit

another roadblock. The Trimark executive who championed it, Jay

Polstein, left the company, so Frida lost its strongest executive ally.

Hayek was frustrated and secretly took the project to Harvey

Weinstein at Miramax. Weinstein liked to nurture young actors, and

Hayek was one of the rising stars in the Miramax stable; the

company had financed many of her early pictures. Miramax was of

course the premier house for venturesome independent films, and

Weinstein immediately responded to the idea of actually producing

the Frida Kahlo project that had been the talk of Hollywood for a

solid decade. Miramax bought it from Trimark and hired Hayek,

Hardin, and Speed, along with Jay Polstein, to produce the picture.

"It cost Miramax a huge amount of money to secure the rights,"

Hardin says gratefully. "But it was Salma who pushed it through."

"Sometimes producers are wary of working with actors," Speed adds.

"But it's been great with Salma because each of us can take turns

being the cheerleader for the project. When one of us gets drained,

one of the others can take over and push for it."

"To me this is not just another movie," Hayek says. "I want to tell

this story about my country and my people. For a couple of decades,

Mexico was an important center where great people from the arts and

politics gravitated. I want to remind the world of that."

Weinstein approached Walter Salles, the director of the Academy

Award-nominated hit, Central Station, to direct Frida. But a prior

commitment prevented Salles from taking the assignment. "Losing

Walter was another blow," Speed sighs. But the producers have

refused to lose hope. Miramax is still enthusiastic about the movie

and has sent the script out to several high-profile directors. "Frankly,

Miramax has too much money invested in it now to give up on it,"

Hayek says. "I know this film will be made." Kahlo, who was famously

cynical and self-deprecating, probably would have been bemused by

all the Hollywood intrigue surrounding her name, but she also might

have been secretly tickled. After all, it is only fitting that her turbulent

life would serve as the backdrop for one of the most wrenching

Hollywood struggles of the last decade. When Kahlo's story finally

does reach the screen, it may be the ultimate revenge of the little

woman who lurked in the shadow of several towering men and finally

overpowered them all.

|